Stagecoaches were a popular form of transportation until networks of railroads slowly replaced them. They appeared in America as early as the mid-1700s when they were little more than a wagon with a simple covering to keep passengers and goods out of the weather. The ride, frequently over narrow, rocky trails, was bone-jarring. They were stifling hot in summer and frigid in winter. Yet, despite some discomfort, stagecoaches were much more convenient than horseback for traveling and sending letters, money, and small goods.

Stagecoaches were primarily used in New England until the early 19th century. Use expanded after 1827, when two men in Concord, New Hampshire, devised a system of resting a coach on two long leather straps, resulting in a swaying, softer ride. The Concord coach became the standard, making travel more comfortable, especially for the long distances to the expanding west.

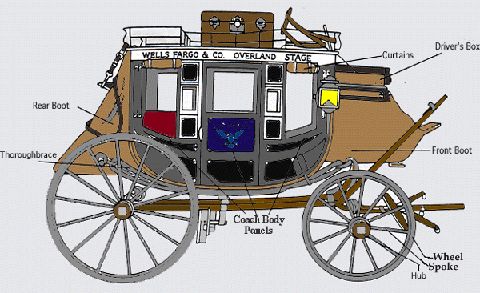

Concord coaches were gentler than previous versions but were small and expensive. They were only 8 ½ feet long and could cost $2,500. Owners jammed goods and people in every available space inside and out to recoup their investment. Stages generally traveled 24 hours a day with brief stops to exchange horses and occasionally for food. Some stations were little more than a cabin, barn, and corral, where the stage stopped for about ten minutes so that stock tenders could change out their horses. Between stations, ever-present dangers of robbery, accident, and attack were well documented, often splashing across newspapers.

Artist unknown

Drivers had to be skillful and brave to travel through wide-open, unprotected country. They found themselves unceasing targets for attack by hostile natives or marauding bandits. In his left hand, a driver held three pairs of reins; in his right, his whip with which he controlled his team of four or six horses or mules. Beside him sat his partner with a rifle.

Nineteen-century accounts give a sense of the experience. In 1842, Englishman Charles Dickens was 30 when he and his wife visited the United States. Most of their travels were on the Eastern seaboard, but on one occasion, they ventured out of the city to the prairie. Although most of his writing was about American culture, his brief descriptions give readers a sense of early stagecoach travel.

Dickens returned to America a second time in 1866. As with his earlier visit, admiring readers mobbed almost to suffocation.

A young Mark Twain came to explore the American West between 1861 and 1867. In his book Roughing It, he wrote imaginative stories of his tour of the “Wild West” by stagecoach. He described the stagecoach as a cradle on leather straps, rocking its passengers to sleep on a peaceful trip.

A New York Times reporter wrote about a much more harrowing journey west in late 1865. Even though accompanied by soldiers, his stagecoach was attacked by resentful natives who stole their horses and threatened their lives. The travelers were bereft for days until resupplied, only to be robbed by armed bandits two days later.

Ben Holladay was known as America’s stagecoach king. He established the Overland Line to California during the 1849 gold rush. In 1861, he won the contract to deliver mail along the Overland Trail, adding six more routes over time. He employed 15,000 workers with 110 Concord coaches. Holladay sold his company to Wells Fargo Express in 1866 for $1.5 million to invest instead in railroads.

Railroads eventually replaced stagecoaches. They were less flexible but faster and more comfortable, but until the arrival of the railroad, stagecoaches were indispensable in transporting people, mail, and goods.